The U.S. will allow more individuals to take methadone at home

The U.S. is set to implement its first major update to methadone regulations in two decades, aimed at expanding access to this life-saving medication starting next month. However, experts caution that the effectiveness of these changes may be limited if state governments and methadone clinics do not take action.

For years, strict regulations mandated that most methadone patients visit designated clinics daily to consume their dose under supervision. These rules, rooted in skepticism toward individuals with opioid addiction, aimed to prevent overdoses and illicit distribution of methadone.

The COVID-19 pandemic shifted this perspective. To curb virus transmission in crowded clinics, temporary rules permitted patients to take methadone unsupervised at home. Research indicated that this practice was safe—overdose deaths and drug diversion rates did not rise, and treatment retention improved. As a result, the U.S. government made these changes permanent early this year, with clinics required to comply by October 2, unless constrained by stricter state regulations. For instance, Alabama, where around 7,000 individuals receive methadone for opioid use disorder, plans to adopt the new flexible guidelines, according to state official Nicole Walden.

“This marks a significant shift in perception,” Walden stated. “People don’t need to show up daily for a medication that can save their lives.”

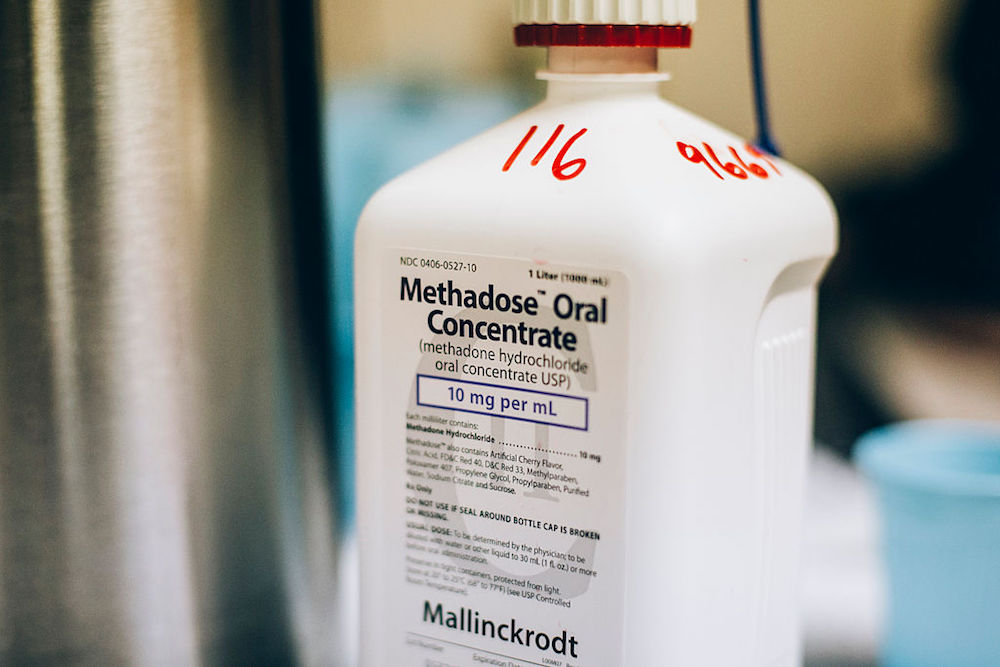

Methadone, an opioid itself, can be dangerous in excessive amounts. When administered correctly, it can alleviate cravings without inducing a high. Numerous studies have shown that it reduces the risk of overdose and the transmission of hepatitis C and HIV. However, it can only be prescribed for opioid addiction through the nation’s 2,100 methadone clinics, which treat nearly 500,000 patients daily. The new federal rules permit stable patients to take home up to 28 days’ worth of methadone. States like Colorado, New York, and Massachusetts are updating their regulations to align with this flexibility, while others, such as West Virginia and Tennessee—states with the highest drug overdose rates—have yet to follow suit.

“Where you live matters,” said Beth Meyerson, a University of Arizona researcher studying methadone policy.

Irene Garnett, a 44-year-old resident of Phoenix, would welcome the option for more take-home methadone doses. Despite being a patient for over ten years, her clinic still requires her to visit twice a week. “It’s just ridiculous,” she remarked. With 28 days of take-home methadone, she believes she could have more freedom and a “more normal quality of life.”

The new rules give clinics considerable discretion over who qualifies for take-home doses, ideally involving collaborative decision-making between doctors and patients. However, financial incentives may also influence these decisions. Frances McGaffey of the Pew Charitable Trusts highlighted that clinic payments often favor in-person dosing, potentially discouraging take-home options.

In Arizona, clinics receive $15 per in-person dose compared to about $4 for take-home doses, prompting the state to explore equalizing these amounts or implementing bundled payments that reflect overall treatment costs. New York’s Medicaid program already utilizes a bundled payment model, eliminating financial incentives for in-person visits.

Longtime methadone patient David Frank, a sociologist at New York University, appreciates his ability to take home four weeks’ worth of methadone wafers. He stated, “I could never have pursued my Ph.D. or conducted research if I had to go to a clinic every day. It’s a night-and-day difference in living a stable, fulfilling life.”

A movement to “liberate methadone” is gaining traction among long-term patients like Garnett and Frank, especially as annual overdose deaths now exceed 107,000. They advocate for legislation allowing addiction specialists to prescribe methadone and pharmacies to fulfill those prescriptions.

While the new federal rules are a step forward, they also introduce additional changes, such as:

- Methadone treatment can begin more quickly, without requiring a one-year history of opioid addiction.

- Counseling can be optional instead of mandatory.

- Telehealth can be utilized for patient assessments, enhancing access for rural residents.

- Nurse practitioners and physician assistants can also initiate methadone treatment.

“It’s up to states to implement these changes to improve access to care,” remarked Mark Parrino, president of the American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence.

Tennessee officials are drafting rules that are even stricter than federal guidelines, proposing increased random urine testing and mandatory counseling for many patients. Critics argue that these proposals are overly punitive and counterproductive.

In states that adopt the new federal rules, implementing these changes may still pose challenges for clinics. Some clinic leaders might resist the patient-centered approach and the legal implications of determining which patients can safely take methadone at home.

“Not all opioid treatment programs operate the same way,” noted Linda Hurley, CEO of Rhode Island’s oldest methadone program, CODAC Behavioral Healthcare.

Historically, clinics have been constrained by stringent regulations. “We’ve regulated them into a corner for years,” said Meyerson. The new rules now allow for a more patient-focused approach.

“The question is,” she concluded, “can they make it work?”